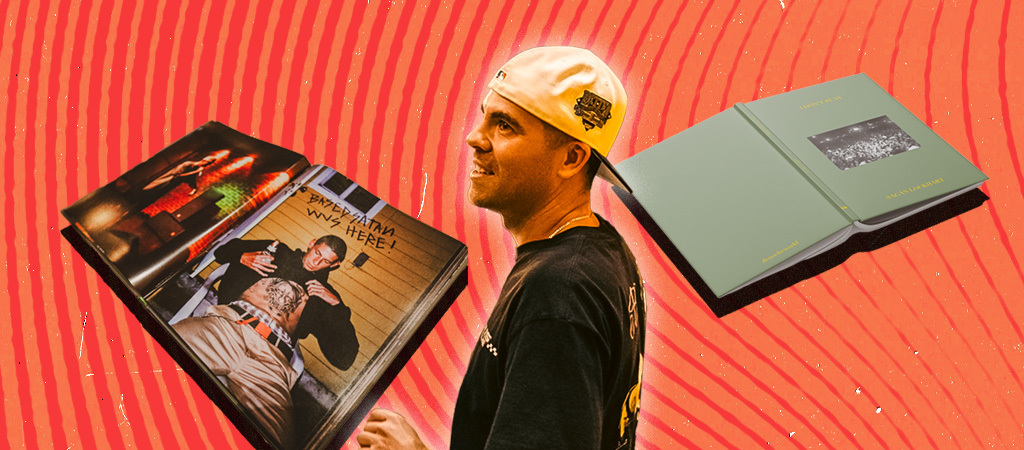

When Creative Director Adrian Martinez started out in the music industry, he had no idea where he’d be today. Doing what he describes as “bits and pieces of the creative process” and capturing content for artists via video and photography was his first glimpse into a future he hadn’t necessarily planned for. “I was doing like a ton of video editing. I got into graphic design,” he tells UPROXX. “I started working on cover art from there. I got into music video direction after a couple of years of being around artists and networking.” Those connections he made combined with a comfort behind the camera – not to mention the symbiotic relationship he was able to easily build between himself and musicians – “snowballed into other opportunities” and he was able to put on live shows for artists.

Fast-forward to now, Martinez has worked with the likes of Rauw Alejandro, Peso Pluma, Bad Bunny, 6lack, and more to bring their creative ideas to life. From 3D animation to branding merch design and experience production, his creative house, STURDY, has become a one-stop shop for musicians who want start to finish creative handling of their campaigns.

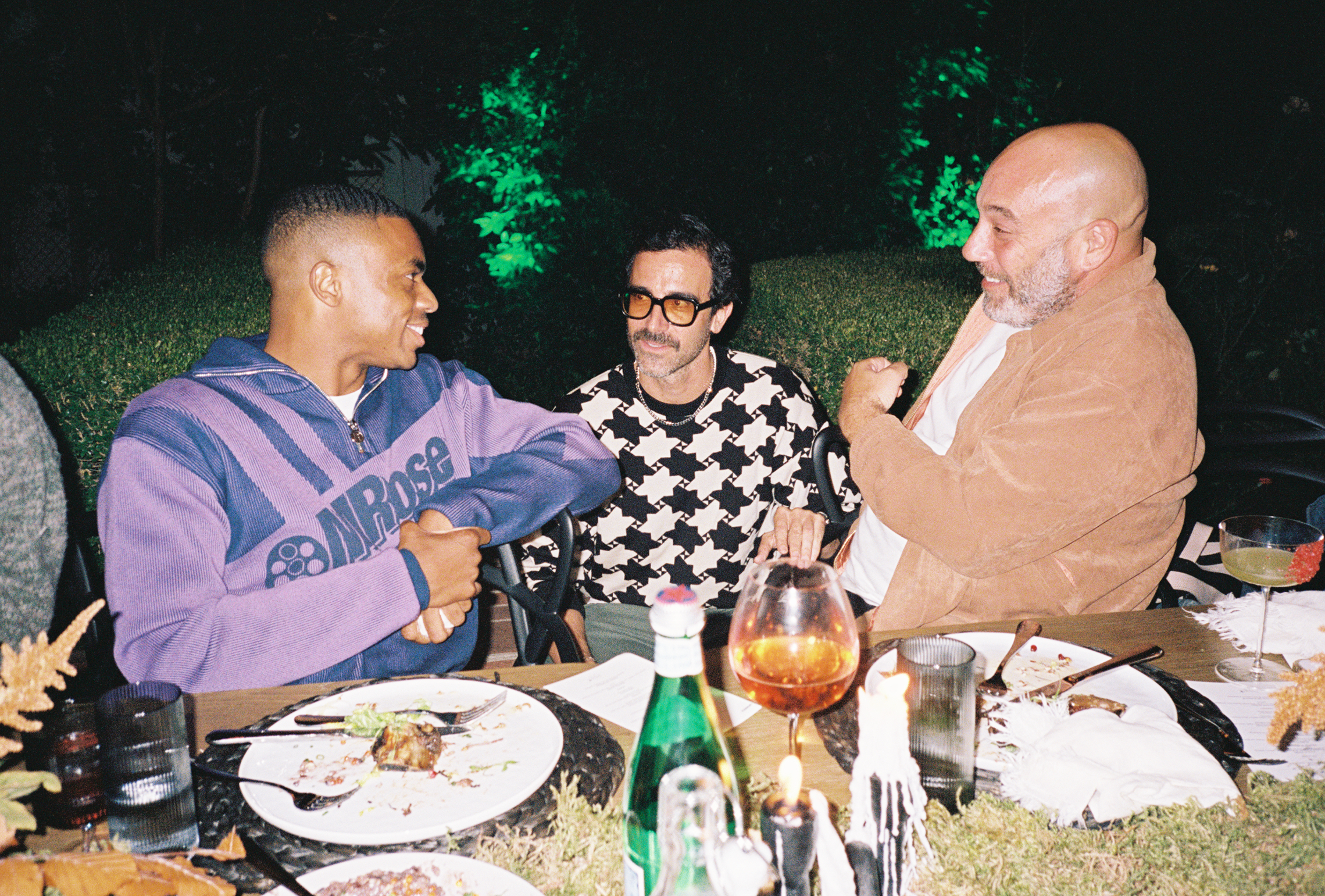

Ahead of receiving the Spotlight Award for excellence in creative direction at the upcoming UPROXX event for the Sound + Vision Awards, we spoke to Martinez about how his creative intuition and love for music pushed him into a self-made career and what he’s most excited to create next.

Is there an early project you worked on that cemented your desire to be a creative director?

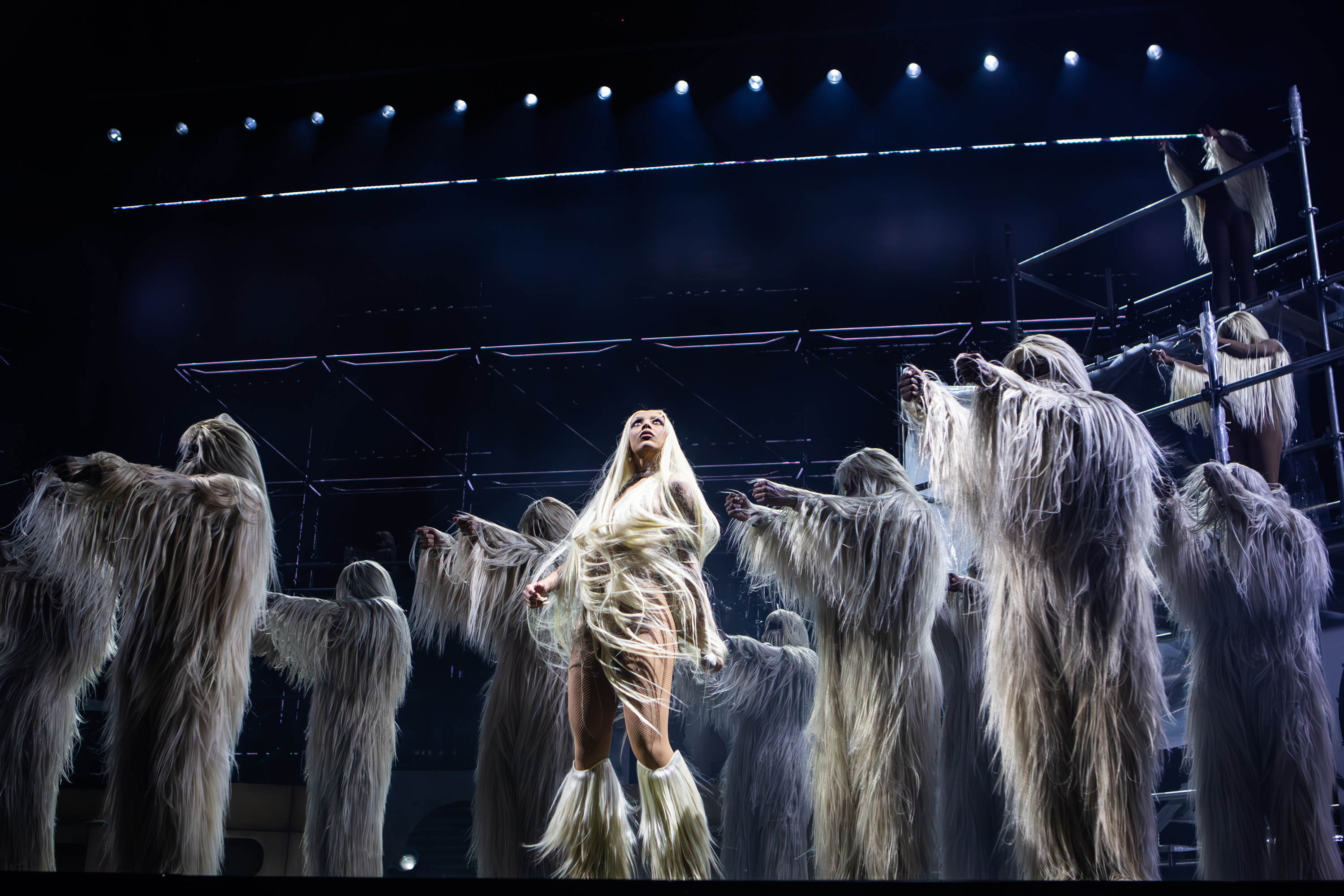

I got an opportunity, which was at the end of 2016, to work with PARTYNEXTDOOR on his second tour. He let me do the creative behind it, let me design it. I had no idea what I was doing, but I was just going to figure it out and had good people working around me on all the other departments of the show. From there, I found out that I enjoyed working on the design side of the show more than capturing it. As a creative director, I’m able to speak to all these different people that work across different mediums and take in different parts of what a campaign is these days — which is everything from cover art to marketing ad mats, tour posters, the music videos, all the way through to the stage design and lighting direction.

When you say you enjoyed the design side more than the capture side, what was it about that experience with PARTYNEXTDOOR that led you to that realization?

On a very basic level, I felt that when I was taking photos, I didn’t enjoy how he was lit. I didn’t enjoy how the lighting was captured. It always felt a little messy and uncurated and it felt like the lights were just there to be there. I felt like he should be standing here at this part of the show or he should interact this way and the lighting should be hitting him from the back so that he has a good rim light. That PARTY show I’m talking about was much more a trial than a success, but it made me open my eyes to what was possible and where I wanted to go.

Do you always work on every aspect of a campaign and all the different facets you mentioned, from tour posters to set designs?

My goal is to be able to do the campaign and its live side. I feel like that’s where the needle really gets threaded in the best way and where I have found the most success. People always do want to piece it together and I understand there are other creatives involved before I get in the mix, there are always other people helping execute things and I think it’s important to be open to the collaborative process. But I try to either keep it to the whole campaign or the whole live show, and if that’s separate, that’s cool. But ideally, like I said, it’s kind of like the more global approach.

You mentioned PARTYNEXTDOOR felt like a trial. What was you first success?

Four or five months later I got an opportunity to work on another OVO SOUND artist’s show. It was Majid Jordan playing at Coachella. That was April of 2017. I felt that through that process I got to know the artists very well. I had a sense of confidence and comfort in being able to ask questions and try to assert my point of view much more than just subsiding to what they wanted.

Also, in between the PARTY tour and the Coachella show I had met a couple of guys that ended up being a co-founder of this company I run called STURDY, and they were really focused on the visual side of the shows. They were doing 3D and 2D animation and I was with them almost every single day. I was soaking up so much. I learned things like a pixel map which is what you use to map content onto screens properly. I picked up new software and started messing with After Effects and seeing what I could do with 3D software. I didn’t realize that it was the very beginning of what we’re doing now. When I look back it’s still one of the shows that stands out to me because it felt like although we were young kids having fun, we were also really into the process. We were very dedicated.

Tell me more about Sturdy, how did it come together?

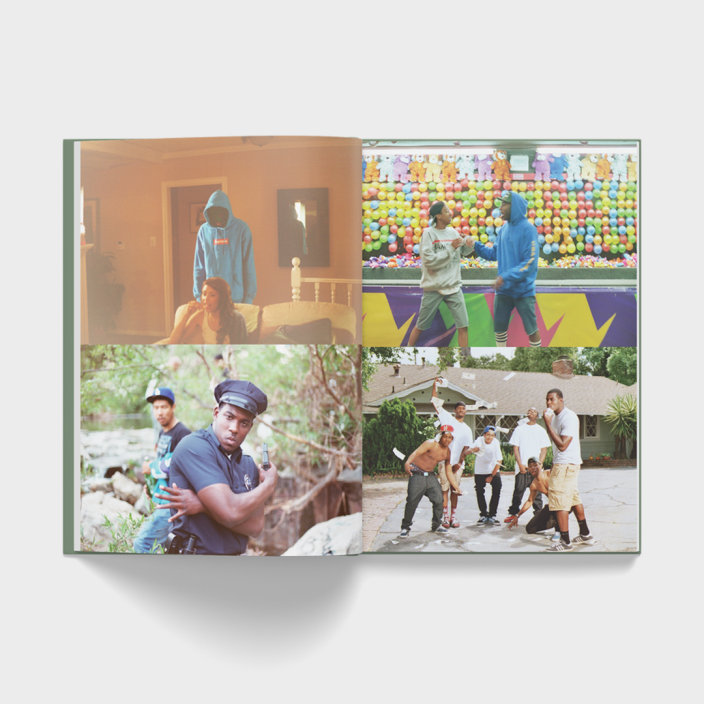

We got to work on a lot of shows really quickly after that, and we started getting opportunities to do visuals and get involved in the creative side of artists’ careers. Things were kind of moving for us pretty rapidly in the summer of 2017. We got to work on Kendrick Lamar’s tour. It was a three-day turnaround on some visuals but we were super stoked and it was awesome to be able to work with Dave [Friley] and Kendrick on that. It gave us a little bit more validation within the industry. And also, I needed more confidence to keep pushing and keep going.

By summer of 2018, we got to work on Drake’s tour visuals and we’re seeing stuff happen at a really high level and felt like we were actually starting to compete with bigger companies and being looked at by bigger clients. We realized that if we were just a bunch of ragtag freelancers, it was just never gonna turn into something real. We also knew we really enjoyed working together and that our team dynamic paired with finding a name that we felt we could stand behind made us want to make it official. By the fall of 2018, we had made STURDY an official thing.

The position of Creative Director can be opaque in some cases, especially when you’re doing so many jobs and wearing so many hats. How do you describe your work to people?

I always say a creative director is not just the person who says this is how we’re going to do it. You’re actually directing creatives. That is what you’re doing. So that means you have a bunch of people that you need to be able to speak to in a way they’ll understand. That translates to the way that they look at the execution, the buttons that they press on their side, and the way they process concepts. And then you have to do that in a bunch of different ways with all these different people. Same with a live show. You have the guys who do visuals, and then you have the guys who are in charge of rigging and that are in charge of making sure that the building can withstand the weight of the screens that are hanging or the lights or whatever. And then you have the lighting designer and you have to make sure that they’re doing things in a way so that the really cool designs and renders that you have in 3D are realistic in real life and the list goes on.

What are you excited to create next?

Without getting super specific, I’ve just got some really exciting tours coming out this next year that are with artists that I love, that I listen to, that I’m fan of. It’s always fun to be able to work with an artist whose music you are a fan of, and you then become part of that picture and help build that world. It’s a privilege for sure.