The Internet went into a frenzy in Spring 2023 when Hulu announced that they would be releasing a documentary focusing on Freaknik, the annual HBCU spring break party in Atlanta that not only defined an era but became a bedrock for the future of the city’s vibrant music scene. The stories of Freaknik have been spread through word of mouth over the years. However, videos and photos from the controversial party seldom surfaced online. The stigma often overshadows the beauty of the annual spring break event in Atlanta and what it actually represents: freedom.

At the helm of Freaknik: The Wildest Party Never Told is P. Frank Williams, a veteran journalist who teamed up with Mona Scott-Young and 50 Cent to produce 2022’s Hip-Hop Homicides. Williams is a West Coast native who studied at San Diego State, though he recalls the early days of Freaknik – when it was a rather innocuous picnic. “It’s really about young Black college students,” P Frank Williams tells HotNewHipHop. “You watch this film, this is about Black joy. It’s about freedom, it’s about fun. It’s not about just somebody turning up or anything negative. This was about younger kids who found their sort of Summer Of Soul, their Woodstock.”

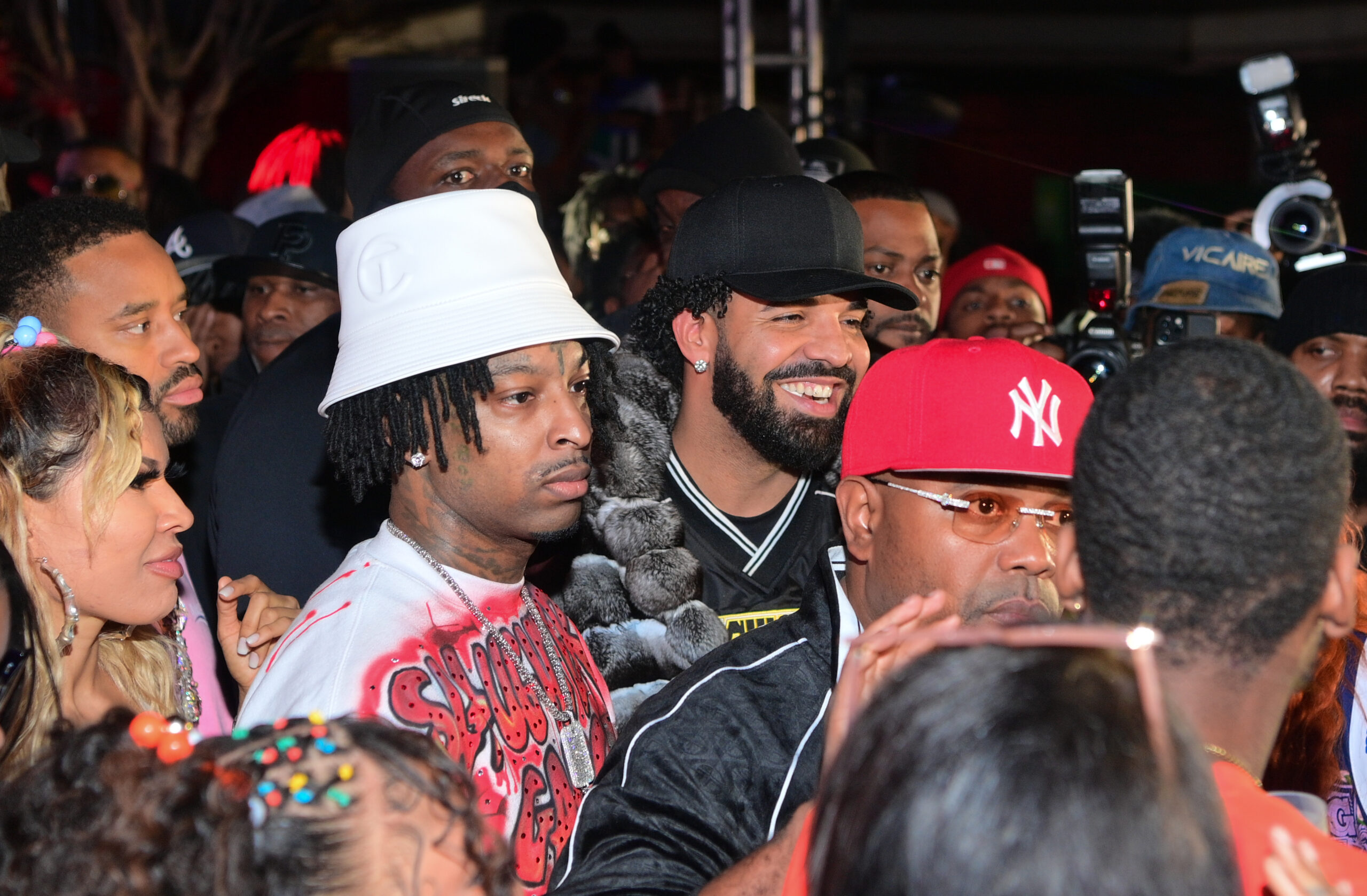

Executive produced by 21 Savage, Jermaine Dupri, and Uncle Luke, Freaknik: The Wildest Party Never Told is an intergenerational documentary that unpacks the legacy of Freaknik with balance. Yes, you’ll see the turn up and some of the more salacious aspects that the event is known for. But, as Williams explains, he serves “the candy and the vegetables” in a way that encompasses the aspects of Black liberation and freedom while ultimately serving as a music documentary. “I really think the end of Freaknik signifies the birth of trap music in the early 2000s,” he said. “As Shanti Das says in the documentary, Southern rap built its foundation on the back of Freaknik.”

We recently caught up with P. Frank Williams to discuss Freaknik: The Wildest Party Never Told, which reached #1 on Hulu in the weekend after its release, and the launch of his new production company, For The Culture By The Culture.

This interview has been edited & condensed for clarity.

Freaknik: The Wildest Party Never Told Is Out Now

I love the way you’re able to unpack so many layers surrounding this. It provides a bigger picture of the significance of Freaknik. Just knowing your history as a journalist in the 90s, what was your personal experience like at Freaknik?

I mean, I was a college student in the early 90’s and attending San Diego State. And I’m in a fraternity so at that particular point, I did pass down around there in like around ‘91 and attended Freaknik. It’s really about young Black college students. So I was a part of that, especially being in a fraternity with The Divine Nine. So, you know, I understood and experienced Freaknik. I didn’t go to it when it was crazy like it became but I do have a cultural understanding of it in real time in real life.

Read More: Jermaine Dupri Sets The Record Straight On Freaknik Documentary

What was the biggest takeaway for you from this documentary?

I think that the origin story, which a lot of people don’t know. It started with these young Black college students in 1983 from the DC Metro Club. I just thought it was a party that they just got cracking. I had no idea that came from actual students who’d had this picnic, and that it became that way. That was one of the big things that I learned.

I also learned – I had no idea that the city of Atlanta, especially the mayor, Bill Campbell, tried so hard to keep Freaknik and try to rebrand as a Black college Spring Break weekend. And he was dealing with the whole city of Atlanta, the white businesses who didn’t necessarily want this African American picnic, and that’s what happened. Those are some of the things that I didn’t really know as much about before I started producing and directing the film.

The documentary is obviously a celebrity-packed affair. Was there anyone who declined or that you weren’t able to interview for this documentary?

I don’t know about that. I mean, I think there’s been some apprehension. You know, a lot of people wanted to participate, especially if you were there. There have been some apprehensions on the part of some of the Black colleges who I think didn’t understand what the film was about, initially. Because of all of the controversy in the media, people thought it was going to be raunchy and salacious, which it’s not if you watch it. It’s not that by no means. Those are some of the people who weren’t able to get in [or that we’d hope] had a little bit more participation.

Outside of that, what was the biggest hurdle with this documentary?

I think just some of the naysayers and people who were trying to label it as something offensive to Black culture, or just that it was gonna be bad for the culture. Also, just people who didn’t understand what it was about. When you say, Freaknik, they think it’s just a street party, or people being negative towards women, or rape or assault. But obviously, it’s about a lot more things than just that, and not just a party. Just overcoming stereotypes was a really tough thing of what people thought it was going to be.

Now that it’s out, how do you feel about the outcome and the reception? Do you feel you accomplished what you set out to do?

I more than accomplished my goal. I mean, this Freaknik documentary has become a global phenomenon, a sort of viral sensation, which I had no idea that was going to happen. And it happened organically. It’s almost like breaking a record back in the day when we first put out the information about it and just announced it. It went crazy without a sizzle reel, without a trailer, without anything. I’m really blessed.

I think the content has connected with a lot of people around the world because hopefully – you watch this film, this is about Black joy. It’s about freedom, it’s about fun. It’s not about just somebody turning up or anything negative. This was about younger kids who found their sort of Summer Of Soul, their Woodstock. So that’s what I want people to takeaway. That this was a story of joy and fun.

As we speak, it’s currently the top trend on Twitter across the globe. One of the running jokes since its announcement was that people were warning their parents, uncles, and aunts about the doc. Have you received any backlash yet for some of the footage included in Freaknik?

I’ve been telling people, obviously, there’s a big brouhaha about some of the people saying that their own to their grandma or their deacon or their pastor or their nurse being portrayed. There have been some people talking to try to block the release. Obviously, they weren’t successful. But I look at it as a badge of honor. To me, that means that she was outside having a good time back in ‘92-’93.

I think it should be a good thing, you know? Your mom, your uncle, your auntie, they all were 21 at one point in their lives, right? I think people were just having fun. I don’t think it should be a negative thing at all. If you got too lit and doing too much, then that might not be good. But overall, I don’t think it’s a negative thing.

This comes shortly after your work on Hip-Hop Homicides with 50 Cent. This is a bit more lighthearted in comparison. However, it’s another project where you worked alongside a few hip-hop heavyweights. 21 Savage, Uncle Luke, and Jermaine Dupri served as executive producers. As a journalist, how critical was their input into creating this documentary and providing a full scope of how Atlanta’s cultural ecosystem works?

I think Jermaine Dupri was key because the rise of So So Def directly parallels Freaknik, literally, from the jump. You know, “Jump” with Kriss Kross to Da Brat to whatever, as I say in the film. He was key because he’s sort of the mayor of Atlanta and sort of the gatekeeper of the culture here. And he actually lived it, even though he’s a little bit younger, and Luke is the soundtrack of Freaknik. He is the guy who turned the party out. He put the freak – as he said – in Freaknik. And so I think you couldn’t have it with those two guys.

A lot of people I’ve heard online – Joe Budden or different people – talking about why is 21 Savage an executive producer. 21 has had multiple birthday parties Freaknik themed which I put in the film. He’s really sort of a disciple of the Freaknik family tree. Without Outkast and Goodie Mob and all those people, there’s no Latto, there’s no 21, there’s no Lil Baby. So I think that it’s fair to say that, even though he wasn’t at Freaknik, he’s still a Freaknik baby. We used them, to be quite honest, as a way to connect with the younger generation. That was part of the reason why he was one of the executive producers.

Freaknik: The Wildest Party Never Told does a great job at capturing the pipeline between Atlanta, Black music, and how all of these things collide with Freaknik. From your perspective – just thinking about Andre 3000’s speech at the Source Awards in ‘95 – how do you think the trajectory of Atlanta’s hip-hop scene would’ve shifted had Freaknik not ended the way it did?

That’s a good question. As I told Dallas Austin last night and told JD and different people I know, without Freanik, the Atlanta music scene does not grow and becomes what it becomes. Because you’ve got all these people to come into the city, you got people discovering the music. You got JD and Dallas building up their labels based on all these thousands and millions of people.

I think that if Freaknik would have kept going, I think you probably would have saw more bass music. I really think the end of Freaknik signifies the birth of trap music in the early 2000s. And you know, in the 90s, it was more about bass music and partying. So, I think that opened the door for trap music.

How do you think Freaknik, especially from its development in the late 80s and early 90s, helped create the cultural connection between the South and other regions, whether the East Coast, the Midwest, or the West Coast? You see footage from ‘94 of Biggie and Craig Mack performing.

One of the points I’m making in the film is the pass-around ability in the 90s. You know, Outkast mixtape, you could put that in your tape deck right there. If you came from Virginia, Florida, Texas, or wherever and you came to Freaknik, you got that music that they were playing in the streets. You took that back to your home. So I think that Southern rap spread through Freaknik.

As Shanti Das says in the documentary, Southern rap built its foundation on the back of Freaknik. And so, Freaknik was spreading Southern rap all over the country, based on people from all over bringing that music back to their city. JD talks about it extensively and so you know, that happened because of Freaknik. Where else could you have hundreds of thousands of people on the street and be able to promote your music?

I think there was an innocence and a beauty of Freaknik, musically, in terms of what we could do and just how the music drove the whole thing. Without the music, there’s no Freaknik. And by the way, I tell people, this is a music documentary. It’s about how Black southern music, especially Hip Hop, drove the culture of Freaknik.

Going back to when you first attended Freaknik, how do you think the entrepreneurship shown during Freaknik reflects the modern state of Atlanta today?

Well, that’s a really good question. That’s one of the best questions I’ve been asked since I’ve been doing this. You know, Atlanta has an entrepreneurial kind of spirit, anyway. I think if you look back to the days in the 60s and how African Americans have always thrived as a Black business here.

If you look at Edgewood, or even Killer Mike with his shop – I think that the young generation, the Gen Z – I have two Gen Z kids – they grew up like, “I don’t have to work for somebody, I don’t have to go get a record label to make it.” They can just do it themselves, they can sell their own merch. They got the internet. The internet has become like a global marketplace to do whatever you want. So I think for Atlanta, the entrepreneurialism that started with JD or different people in the 90s only quadrupled, I mean, tenfold with Gen Z because there are more opportunities, especially because of the internet.

How do you think people’s attitudes about Freaknik and their involvement have changed over the years? From being a celebratory party to becoming taboo, to now, where it carries this very significant legacy.

I think it’s all about perception, right? Back in the day, it was just thought of as this fun turn up thing. The announcement of this documentary [had] people thinking I was going to do a salacious over-the-top, kind of like exposé. Now, I think the people actually watching the film see that it’s the candy and the vegetables. I gave you all the candy, which is the party and the turn up, the girls, the getting lit, the cars. But there’s a vegetable which is Black economic freedom. Young Black people finding themselves in a college way, you know? Young ladies liberating themselves sexually. You know, political strife, which is the Black police in Atlanta against these young people party. And so hopefully, I gave you a full-course meal, not just like an appetizer, you know?

The documentary explains how things got a little hectic, Atlanta tried to clamp down, and things didn’t move forward the way they wanted to. Now, we’re seeing a similar situation happen in Miami Beach for Spring Break. Do you see the parallels between the two?

300%. I think some of the issues that happened back then – it’s unfortunate that some of the racism from society, from police – that plague some of the young Black people of Freaknik of the 90s is still happening today in 2024. It only speaks to, unfortunately, how far we haven’t progressed as a race and as a culture of human beings. It’s not something I wanted to show that it’s still the same, but it’s the truth.

The former mayor of Atlanta, Bill Campbell, appears in the documentary and still feels strongly about how he handled Freaknik. Then, you have Stacy Lloyd. She details being assaulted at Freaknik, and expresses her disappointment in law enforcement and the politicians. From your conversations with both, what do you think could’ve been done differently to protect Black women and Freaknik attendees at large from some of the chaotic elements that plagued the event?

You know, it’s a really tough one. I think we definitely don’t want our sisters ever being assaulted by us, or anyone. I mean, not feeling safe. Again, as I said, some of the elements that came in later were not the best elements. And when those kinds of elements creep into things, you can’t control that. I do think that Freaknik was a big street party that cops were trying to figure out how to navigate.

So to Stacy’s point, she felt that law enforcement failed her. In some ways, they did because they didn’t protect her from being assaulted, and there weren’t enough police on the street to stop some of the bad actions of the predatory men. I do think that we need to find a way to balance that and not make it in a way where law enforcement is overbearing, but people feel safe. And so regretfully, that happened, and I think because of that, that’s why Freaknik had to end.

What was the process like getting Stacy Lloyd in the documentary?

We were able to put a post out on Facebook. I had a researcher who started looking around for young ladies or people who had situations. We spoke to a few people, and we ended up working with her.

Was she initially open to appearing in the documentary?

I mean, it was a little bit traumatic, obviously. You can imagine if you’re revisiting yourself being assaulted 25 years ago, but she was a soldier and a really strong person. And I think that what she did was have a voice for women and Black women by telling her story, which was an important story because not everything in Freaknik was piece to pie. There was a lot of negative things that went on, as well.

By the end of the documentary, Freaknik is described as “something that needs to die” yet we’ve seen its resurgence in recent years. How do you see the legacy of Freaknik carrying on with the younger generation, especially those who were barely alive during its peak?

I think the nostalgia and the legacy of Freaknik are one of Black joy and freedom. And I think there’s a lot of young people who want to go back to that and I think that that’s why it’s connecting. This film is a multi-generational connection. A lot of times, things are for the older people in hip-hop or the golden era. Sometimes the younger – the Tekashi stuff is for a different demo. I think this is a universal story because it’s about it’s about joy, it’s about fun, it’s about hanging out with your friends, it’s about meeting girls, it’s about girls meeting guys, you know what I mean?

So I think that themes are universal and I think a lot of the people, like the Drake’s and the Latto’s and the Lil Baby’s and the 21’s, they want to go back to that time because that would seem like a time when it was safer and more fun. So I’m glad that the film brought so much nostalgia, but also, you know, connected with a whole new generation.

Do you think Freaknik could ever be what it was back in the day?

No, I mean, I think that was a that was a genie in a bottle. It was a time capsule because the world was a different place. Everybody wasn’t on their phone trying to snap a selfie. People weren’t so connected to the internet; people were in the moment a lot more. Things were a lot safer, even though it was dangerous, sometimes gang violence but Freaknik itself, even though there were some moments, was not a dangerous event. And so I think that in that regard, it couldn’t come back.

But I do think, the 21 Savage birthday party, where he had it in a controlled environment with a lot of police. There’s only one way in one way out. He had all the phone booths, and the cars and the girls and all that. Like, that’s sort of what it could be today in a controlled situation. But I don’t think it could be 250,000 people all over the city of Atlanta going crazy. That couldn’t happen again.

Final question – you just launched your new production company, For The Culture By The Culture. Tell me more about what we could expect from this new venture.

For The Culture By The Culture is, you know, obviously, I’ve released that talking about the new company. Just want to create more opportunities for People Of Color to tell their stories. You know, I got a Busta Rhymes doc that I’m doing that’s in motion, a project or two on Tubi and different stuff. I just want to use this opportunity to create more stories about hip-hop, Black political culture or whatever it may be. And so that’s my goal, to continue to tell the stories about our culture, whether it be on a large streamer like Hulu or Disney or Tubi or stuff that I create for my own platform. So yeah, man, we’re for the culture, by the culture.

The post What Happened To Freaknik? How The Annual Party Helped Birth Trap Music appeared first on HotNewHipHop.

(@Kilahh_Tequila)

(@Kilahh_Tequila)

(@Dro2H)

(@Dro2H)  (@brownandbella)

(@brownandbella)