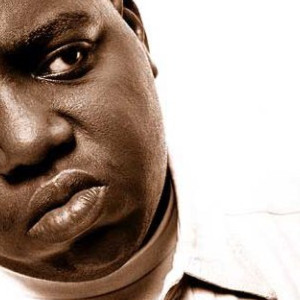

To be perfectly honest — following the example set by the late, great Christopher Wallace himself — the world didn’t need another Biggie Smalls documentary. The details of The Notorious B.I.G’s life and death have been thoroughly picked over by now, nearly 23 years later, with dozens of works from books and films to podcasts and television series providing reams of conjecture, speculation, and solemn reflection on the gritty self-styled King Of New York who rose from the streets of Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn to become the epitome of the “ashy to classy” archetype established by hip-hop in the decades since.

That didn’t stop Netflix from releasing yet another entry to the growing canon of works about the Brooklyn big man this week, the hyperfocused and touchingly graceful Biggie: I Got A Story To Tell. But where this more down-to-earth production differs from those that came before it is its intent attention to Christopher, the person at the center of the mythos, rather than on the lurid details of his beef with Tupac or his violent, unsolved death in Los Angeles on March 9, 1997.

Nearly an hour of the film’s 90-minute runtime is devoted to Wallace’s life before he released his game-changing debut album, Ready To Die, in 1994. Through interviews with his mother, Voletta Wallace, and unseen archival footage provided by Big’s right-hand man, Damion “D-Roc” Butler, a clearer picture of Christopher Wallace is developed throughout. From his trips to visit his mother’s family in her native Jamaica to the early musical education he received from a neighbor, jazz musician Donald Harrison, we can see the foundation of his unique, seismic flow and outsized stage persona.

In one particularly engaging scene, Harrison breaks down how Big’s flow imitated the rat-a-tat tapping of a bebop drummer, his percussive delivery playing invisible notes as he freestyled on corners. Scenes like this one offer new lenses through which to view iconic moments like Big’s sidewalk battle with Supreme; while familiarity can breed contempt, Harrison’s quick jazz lesson gives viewers new context and deeper understanding of not just the battle, but Big’s songwriting approach as a whole.

The film also touches on Big’s time spent dealing drugs around the corner from the apartment he shared with his mother, this time with the added texture of commentary from the men who stood out there with him. One, an elder ex-hustler named Chico Del Vec, spends much of his intro fussing at the cameraman that he doesn’t want to get into details of “the game” before crisply detailing the mentality that drove young boys like Big and his friends into it with a veteran’s well-weathered perspective. “If you wasn’t into hustling, good in sports, or going to school, you was a nobody,” he summarizes.

But Big’s cohort is also clear-eyed about their bad decisions as well. Here, just 30 minutes in, the film crystallizes the core concepts of hip-hop, its artifice and artfulness, its originality and creativity, and its universality. These 14-year-old kids had no clue of the world beyond their borough; as Big explains in an interview clip of his breakout hit “Juicy,” he didn’t know that there was money in rap. He only knew what he saw on the covers of magazines, that his favorite rappers wore gold chains and posed with flashy new cars. It never occurred to him that his hazy childhood vision of becoming an art dealer could be every bit as lucrative (and, in truth, probably more so, the way contracts were structured in those days).

It’s what makes Big — and his story — the perfect avatar of hip-hop, from its artists to its fans. He could have been any one of them. By focusing on his humble beginnings, I Got A Story To Tell finally humanizes him in a way few of the biopics or mini-series ever could because the focus shifts away from the big, pivotal moments of a hip-hop legend’s life to tell a simpler story about a boy with a dream, who hung out with his friends, got into trouble, got scared straight by a tragic loss, and persevered through normal, relatable doubts to remain as close to still being the person he always was when fame finally found him.

Of course, staying away from the more familiar notes of his greater life story allows the film to polish his rough edges, such as his alleged abuse of his romantic partners — which again, reflects a broader tendency in hip-hop and pop culture of flattening and simplifying complicated people. At one point early on, Sean Combs — you know he had to make an appearance here, although the film wisely minimizes his presence — notes, “You always were able to hear some remnants of previous rap artists. This guy, I don’t know where he came from with his cadence, with his rhythms, with his sound…” From Compton rapper King Tee, Puff.

But, then again, those rough edges are plain to see in other places. The point of Netflix’s documentary is to add another layer of context and humanity to the legend. It explains a little more of the hows and whys surrounding Big. When the film ends — as the 2009 biopic Notorious did — just after Big’s celebratory 1997 memorial in his hometown, it does so with a better understanding of the person who actually died, beyond the loss of his musical potential. So, did the world need another Biggie Smalls documentary? The answer is still “no,” but we’re all better for this one’s existence.

Some artists covered here are Warner Music artists. Uproxx is an independent subsidiary of Warner Music Group.